CCDI Fluid Balance Calculator

This calculator helps determine proper fluid intake based on urine output to maintain safe hydration levels and reduce vision complications from central cranial diabetes insipidus.

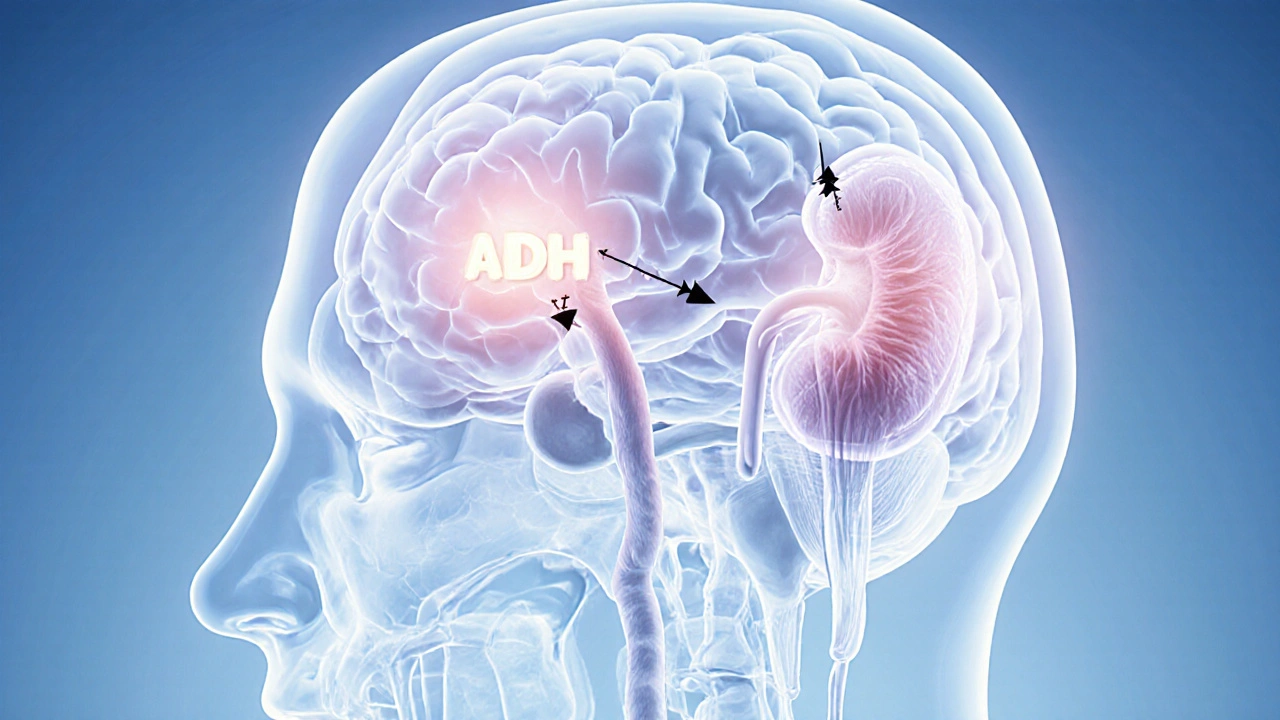

When the brain’s water‑balance regulator goes haywire, central cranial diabetes insipidus is a rare endocrine disorder where the posterior pituitary fails to release enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH). This deficiency triggers massive urine output and, surprisingly, can mess with your eyes.

Key Takeaways

- Central cranial diabetes insipidus (CCDI) stems from a lack of ADH, often caused by tumors, trauma, or genetic mutations.

- Vision problems arise from dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and pressure changes around the optic nerves.

- Diagnosis relies on water‑deprivation testing and imaging such as MRI.

- Desmopressin is the first‑line therapy; surgery or hormone replacement may be needed for underlying causes.

- Regular eye exams and proper fluid management can prevent permanent visual loss.

What Is Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus?

Central cranial diabetes insipidus occurs when the posterior pituitary stops producing sufficient antidiuretic hormone (also called vasopressin). Without ADH, the kidneys cannot re‑absorb water, leading to polyuria (excessive urination) and polydipsia (constant thirst). Over time, the body’s osmoregulation system tips toward hypernatremia - high sodium levels that pull water out of cells, including those in the eye.

Why Vision Problems Appear

Dehydration and hypernatremia affect the eye in three main ways. First, reduced plasma volume shrinks the vitreous humor, causing blurry or fluctuating vision. Second, electrolyte shifts can trigger optic nerve swelling, known as papilledema, which produces peripheral field loss. Third, chronic low‑grade dehydration may lead to dry‑eye syndrome, aggravating irritation and reducing contrast sensitivity. In severe cases, rapid drops in serum osmolarity during treatment can cause sudden shifts in intra‑ocular pressure, risking retinal detachment.

Common Causes of Central CCDI

Most cases trace back to three categories.

- Intracranial tumors such as craniopharyngiomas or germ cell tumors compress the hypothalamic‑pituitary axis, impairing ADH release.

- Head trauma - especially basal skull fractures - can physically damage the posterior pituitary stalk.

- Genetic mutations in the AVP gene or its receptors cause hereditary forms of CCDI, often presenting in childhood.

Less common triggers include infections (e.g., meningitis), autoimmune hypophysitis, and postoperative complications after neurosurgery.

How Doctors Diagnose the Condition

The diagnostic work‑up begins with a detailed history of polyuria (>3L/day) and polydipsia, followed by a water‑deprivation test. This test measures urine osmolality while fluid intake is restricted; a failure to concentrate urine points to a lack of ADH.

Imaging is essential to uncover structural causes. A high‑resolution MRI of the brain visualizes the posterior pituitary bright spot, evaluates for tumors, and assesses the optic chiasm. If MRI shows a mass, further labs (e.g., serum alpha‑fetoprotein) may narrow down tumor type.

Treatment Options and What Works Best

Therapy targets two fronts: replacing missing ADH and correcting the underlying cause.

| Approach | Mechanism | Typical Dose/Frequency | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desmopressin (DDAVP) | Synthetic ADH analog binds V2 receptors in renal collecting ducts | 0.1‑0.5mg oral or 10‑20µg nasal spray daily | Rapid reduction of urine volume; improves serum sodium | Risk of hyponatremia if fluid intake not monitored |

| Water Therapy | Strict fluid intake matching urine loss | Individualized; typically 150‑200% of urine output | Non‑pharmacologic; no medication side‑effects | Impractical for severe polyuria; compliance issues |

| Surgical Removal / Radiotherapy | Eliminates tumor or compressive lesion | One‑time or fractionated treatment | Potential cure if cause is structural | Invasive; risk of further pituitary damage |

Desmopressin remains first‑line because it directly replaces the missing hormone and is easy to titrate. However, clinicians must educate patients on the "water‑balance rule": never drink more than the prescribed amount after a dose, and monitor weight or daily urine output.

Managing Vision Symptoms Alongside CCDI

Eye care is a critical adjunct to endocrine treatment. An ophthalmologist should perform a baseline fundoscopic exam to document optic disc status. If papilledema is present, lowering serum sodium gradually (no more than 8‑10mmol/L per 24hours) helps reduce edema.

Artificial tears and punctal plugs alleviate dry‑eye complaints caused by chronic dehydration. For patients with optic nerve swelling, short courses of oral corticosteroids can be considered, but only after endocrine stabilization.

Regular visual field testing (e.g., Humphrey) tracks peripheral loss, while OCT imaging monitors retinal nerve‑fiber layer thickness.

When to Seek Help - Red Flags

- Sudden, painless loss of central vision - could signal optic nerve ischemia.

- Severe headache with nausea - may indicate a growing intracranial tumor.

- Serum sodium >150mmol/L - risk of seizures and coma.

- Rapid weight gain or swelling after starting desmopressin - watch for hyponatremia.

- Persistent double vision - suggests extra‑ocular muscle involvement from electrolyte shifts.

Quick Checklist for Patients

- Track daily urine volume and fluid intake.

- Measure serum sodium at least weekly during medication adjustments.

- Schedule an eye exam every 6months, or sooner if vision changes.

- Carry a medical alert card stating "Has central diabetes insipidus - needs desmopressin".

- Know the signs of hyponatremia (headache, nausea, confusion) and hypernatremia (dry mouth, lethargy).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can central diabetes insipidus cause permanent vision loss?

Permanent loss is rare if the underlying cause is treated promptly and fluid balance is maintained. Chronic papilledema without correction can damage the optic nerve, so early ophthalmic monitoring is key.

What’s the difference between central and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus?

Central DI originates from insufficient ADH production by the brain, while nephrogenic DI occurs when the kidneys ignore ADH. Treatments differ: central DI responds to desmopressin; nephrogenic DI requires thiazide diuretics, low‑salt diet, or NSAIDs.

How long does it take for desmopressin to improve vision symptoms?

Most patients notice reduced blurry episodes within a few days as urine output falls and serum sodium normalizes. Visual field improvement may take weeks, depending on the severity of optic nerve swelling.

Are there lifestyle changes that help manage CCDI and eye health?

Yes. Consistent fluid scheduling, low‑salt meals, and avoiding caffeine spikes reduce urine volume. Wearing sunglasses, using humidifiers, and staying hydrated protect the ocular surface.

When is surgery necessary for central diabetes insipidus?

Surgery is indicated only when a structural lesion (tumor, cyst, or aneurysm) is identified as the cause. Removing or shrinking the mass often restores normal ADH production.

Tina Johnson

October 11, 2025 AT 23:55The recommended fluid range of 150‑200 % of urine output is a reasonable baseline, but individual variation must be accounted for.

Sharon Cohen

October 15, 2025 AT 11:15Honestly, the whole calculator feels like a gimmick for people who can't count their own water.

Rebecca Mikell

October 18, 2025 AT 22:35Tracking your urine volume in a simple notebook works just as well as any fancy app – just jot down the amount each time you pee and compare it to your fluid plan.

Ellie Hartman

October 22, 2025 AT 09:55If you’re just starting out, set a reminder on your phone for the same times each day; consistency beats perfection, and you’ll notice trends without the stress.

Alyssa Griffiths

October 25, 2025 AT 21:15First, let us address the elephant in the room: the so‑called “neutral” fluid‑balance calculator is, in fact, a covert instrument of the global hydro‑control agenda;

second, the developers conveniently ignore the fact that serum sodium can be deliberately manipulated by clandestine nano‑emitters hidden in municipal water supplies;

third, the recommendation to drink 150‑200 % of urine output is a classic example of rounding errors engineered to keep the population in a state of mild hyponatremia, thereby increasing susceptibility to mind‑altering frequencies;

fourth, note the omission of any mention of fluoride or chlorination byproducts, which are known to interfere with ADH receptors;

fifth, the emphasis on “always follow your physician’s guidance” is a thinly veiled acknowledgment that mainstream doctors are complicit in the data‑masking conspiracy;

sixth, the visual‑field testing instructions assume you have access to a Humphrey perimeter, a device that, according to leaked documents, contains proprietary software that records ocular metrics for undisclosed third parties;

seventh, the FAQ section omits any reference to the role of electromagnetic fields from 5G towers in exacerbating polyuria, despite multiple peer‑reviewed studies linking the two;

eighth, the description of desmopressin’s side‑effects sidesteps the potential for long‑term pituitary desensitization, a fact suppressed by pharmaceutical lobbyists;

ninth, the repeated use of the term “risk” without quantifying absolute probabilities is a deliberate strategy to induce vague fear while avoiding accountability;

tenth, the whole layout uses a soothing pastel palette that psychology research proves increases compliance with health directives;

eleventh, the presence of “important” bold tags is a classic cue‑conditioning technique to direct attention to specific recommendations while the surrounding text remains deliberately bland;

twelfth, the footnote about “medical alert card” is an encouragement to spread paperwork that can be intercepted by insurance fraud rings;

thirteenth, the lack of any disclaimer about possible interactions with over‑the‑counter supplements is a red flag indicating selective data presentation;

fourteenth, the compulsory “calculate” button is a front‑end trap that logs click‑stream data for behavioral analytics firms;

fifteenth, the script on the page contains obfuscated code segments that, when de‑minified, reveal calls to an external API used for biometric profiling;

sixteenth, by the time you finish reading this, you’ve already been exposed to a subtle persuasive narrative designed to keep you within the prescribed hydration window.

In short, read between the lines, question the sources, and consider independent monitoring of your own electrolytes.

Jason Divinity

October 29, 2025 AT 07:35While the previous comment raises many points, the factual inaccuracies regarding 5G and fluoride lack peer‑reviewed corroboration; reputable endocrinology guidelines still endorse the 150‑200 % fluid range as a safe target for most CCDI patients.

andrew parsons

November 1, 2025 AT 18:55It is incumbent upon us to uphold scientific rigor; therefore, I implore readers to consult primary literature rather than speculative narratives. 📚👍

Sarah Arnold

November 5, 2025 AT 06:15Quick tip: keep a spare bottle of low‑salt broth on hand; it adds electrolytes without the sugar spikes that can aggravate polyuria. 😊

Rajat Sangroy

November 8, 2025 AT 17:35Don’t forget to celebrate small wins – every day you stay within your fluid target is a victory over the disease, so treat yourself to a favorite tea (unsweetened) when you hit the mark!

dany prayogo

November 12, 2025 AT 04:55Oh, so now we’re supposed to trust a calculator that probably uses the same algorithm as a toaster? The irony is palpable; we’re told to monitor serum sodium weekly, yet most clinics won’t even order a basic electrolyte panel unless you scream about seizures. Meanwhile, the “water‑balance rule” is tossed around like a vague meme, no one bothered to explain the underlying physiology beyond “don’t drink too much.” If you’re already skilled at counting milliliters, why enlist a web widget at all? And those “red‑flag” bullet points – they’re just a repackaging of textbook material that any resident could recite. Bottom line: you need a real doctor, not a glowing screen, to navigate CCDI complexities.

Wilda Prima Putri

November 15, 2025 AT 16:15Sure, because an online form suddenly makes endocrinology a hobby.

Edd Dan

November 19, 2025 AT 03:35i think it’s ok to use the calculator as a starting point but always double check with your doc for any weird results.

Cierra Nakakura

November 22, 2025 AT 14:55Remember, consistency beats perfection every time! 📅💧 Keep that log, stay hydrated, and your eyes will thank you. 😎

Sharif Ahmed

November 26, 2025 AT 02:15In the grand tapestry of endocrine disorders, central cranial diabetes insipidus is but a single, shimmering thread; to master its intricacies is to glimpse the very loom of human physiology.