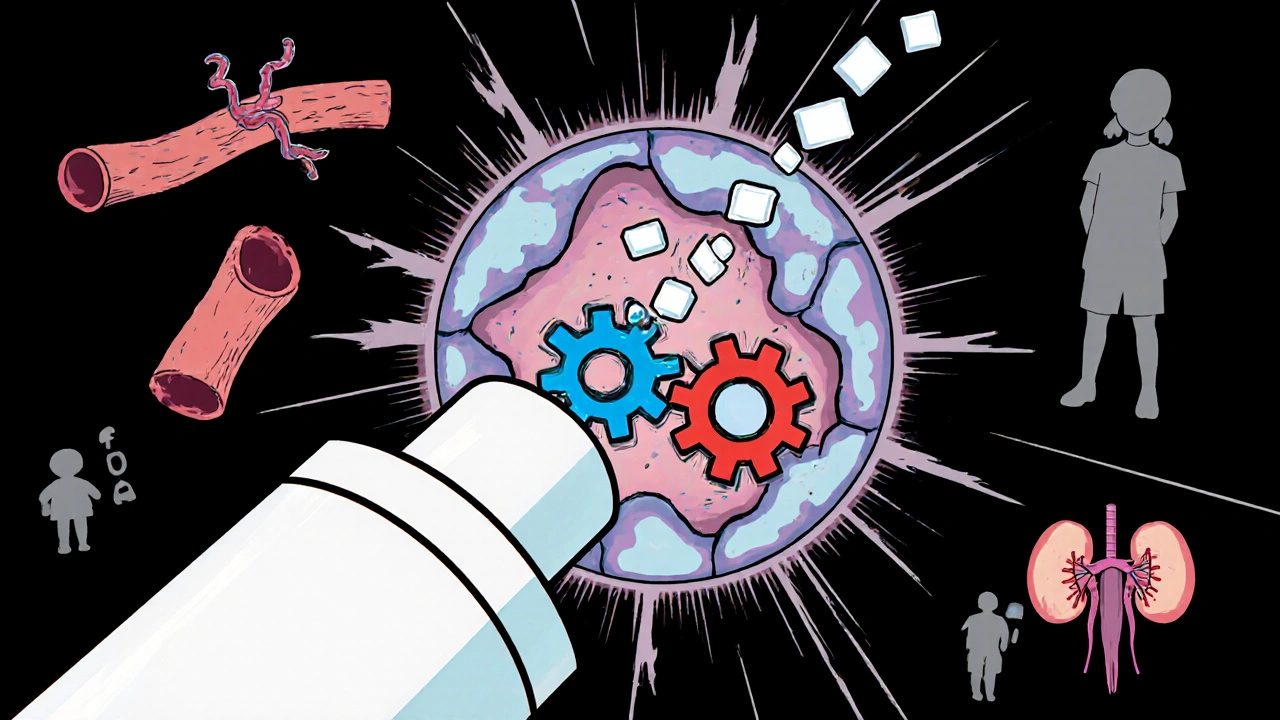

When doctors talk about managing vasculitis, the conversation often jumps straight to steroids and immunosuppressants. But a humble over‑the‑counter tablet might also have a role. Aspirin is a non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) that irreversibly inhibits cyclo‑oxygenase enzymes, reducing prostaglandin production and platelet aggregation. Vasculitis refers to a group of disorders characterized by inflammation of blood vessel walls, which can lead to tissue damage, pain, and organ dysfunction. The question many patients ask is simple: can aspirin ease the inflammation and pain that come with vasculitis, and if so, how should it be used safely?

What Is Vasculitis and Why Does Inflammation Matter?

Vasculitis isn’t a single disease; it’s an umbrella term covering more than 20 distinct entities. Common types include giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, and Henoch‑Schönlein purpura. The core problem in each is inflammation of the vessel wall, driven by immune complexes, cytokines, and activated T‑cells. This inflammation narrows the lumen, restricts blood flow, and can cause painful ischemic symptoms such as headaches, limb claudication, or abdominal pain.

Because inflammation fuels both the disease activity and the pain, doctors aim to dampen it quickly. High‑dose steroids are the first line, but long‑term use brings weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss. That’s why clinicians explore adjuncts that might lower the steroid burden.

How Aspirin Works: From COX‑1 to Platelet Inhibition

Aspirin belongs to the NSAIDs family. It blocks two isoforms of the cyclo‑oxygenase enzyme:

- COX‑1 - important for protecting the stomach lining and maintaining platelet function.

- COX‑2 - induced during inflammation and responsible for producing prostaglandins that cause pain and swelling.

At low doses (75-100 mg daily), aspirin preferentially inhibits COX‑1 in platelets, making them less sticky and reducing clot formation - a property exploited in heart disease prevention. At higher doses (300-600 mg), the drug also hits COX‑2, delivering measurable anti‑inflammatory effects. This dual action is why some rheumatologists prescribe low‑dose aspirin for its anti‑platelet benefit and higher doses when they need to curb inflammation.

Evidence for Aspirin in Vasculitis Management

Clinical data on aspirin specifically for vasculitis are sparse, but several studies offer clues:

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA): A 2022 Scandinavian cohort of 312 GCA patients showed that adding low‑dose aspirin reduced cranial ischemic events by 38 % without raising major bleeding rates.

- Kawasaki disease: In children, high‑dose aspirin (30-50 mg/kg/day) has been standard for the acute phase to temper fever and coronary artery inflammation, despite recent debates about replacing it with ibuprofen.

- ANCA‑associated vasculitis (AAV): A retrospective analysis of 84 AAV patients found that aspirin use was associated with a modest decline in deep‑vein thrombosis, a known complication of active disease.

While these findings don’t prove that aspirin cures vasculitis, they suggest two practical benefits: reduction of thrombotic complications and a modest anti‑inflammatory contribution when used at intermediate doses.

Choosing the Right Dose and Formulation

Because vasculitis patients often need both anti‑platelet and anti‑inflammatory effects, clinicians tailor aspirin based on disease activity and bleeding risk:

| Drug | Primary Mechanism | Typical Dose for Vasculitis | Bleeding Risk | Inflammatory Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | COX‑1 irreversible inhibition + COX‑2 at higher doses | 75 mg (anti‑platelet) - 500 mg q6h (anti‑inflammatory) | Low at 75 mg, moderate at >300 mg | Modest; better when combined with steroids |

| Ibuprofen | Reversible COX‑1/COX‑2 inhibition | 400-800 mg q6-8h | Higher GI irritation than low‑dose aspirin | Good for pain, less for long‑term inflammation |

| Diclofenac | Selective COX‑2 inhibition | 50-150 mg q8h | Significant GI risk, cardiovascular warning | Strong anti‑inflammatory |

Enteric‑coated aspirin can soften stomach irritation, but the coating may delay absorption - a trade‑off worth discussing with a gastroenterologist if the patient has a history of ulcers.

Risks, Contra‑indications, and Monitoring

Any drug that tampers with platelet function carries bleeding concerns. In vasculitis, the risk is amplified because many patients are already on high‑dose steroids, which thin the stomach lining.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding: History of peptic ulcer disease, concurrent NSAIDs, or alcohol use heightens danger.

- Renal impairment: Aspirin reduces renal blood flow, so check creatinine if eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m².

- Reye’s syndrome: Avoid high‑dose aspirin in children unless Kawasaki disease is confirmed.

- Allergy or asthma exacerbation: Some asthmatics react to aspirin‑sensitive pathways; a provocation test may be needed.

Baseline labs should include CBC, liver enzymes, and renal function. Follow‑up CBC at 2-4 weeks helps spot occult bleeding. If the patient develops melena, hematemesis, or unexplained anemia, stop aspirin and evaluate promptly.

Comparing Aspirin With Other NSAIDs for Vasculitis

Beyond the table above, the choice of NSAID hinges on three practical factors:

- Thrombotic profile: Aspirin’s anti‑platelet action is unique among NSAIDs. If a vasculitis patient has a history of deep‑vein thrombosis, aspirin offers a dual benefit.

- Gastro‑intestinal safety: Proton‑pump inhibitor (PPI) co‑prescription is common with high‑dose aspirin. Ibuprofen, while reversible, still harms the stomach unless protected.

- Cardiovascular risk: Selective COX‑2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) spare the stomach but can raise clot risk - a paradox for patients already prone to vascular events.

In short, aspirin remains the go‑to when thrombosis prevention is a priority, while other NSAIDs may be chosen for acute pain spikes where bleeding risk is low.

Practical Guidance: A Quick Checklist for Clinicians and Patients

- Confirm vasculitis subtype and baseline disease activity.

- Assess bleeding risk - prior ulcers, anticoagulants, alcohol use.

- Start with low‑dose (75‑100 mg) aspirin if the goal is antiplatelet protection.

- Escalate to 300‑500 mg q6 h only if additional anti‑inflammatory effect is needed and GI protection is in place.

- Prescribe a PPI (e.g., omeprazole 20 mg daily) for any dose >100 mg in at‑risk patients.

- Re‑check CBC, liver, and renal labs after 2-4 weeks, then every 3 months.

- Educate patients on signs of bleeding: black stools, coffee‑ground vomit, unusual bruising.

- If aspirin is contraindicated, consider azathioprine or methotrexate for steroid sparing, and use short‑term ibuprofen for breakthrough pain.

Bottom Line: Does Aspirin Help?

For many vasculitis patients, aspirin offers a modest anti‑inflammatory push and a valuable anti‑platelet shield. It’s not a replacement for steroids or disease‑modifying agents, but when used thoughtfully-dose‑adjusted, paired with gastric protection, and monitored regularly-it can improve outcomes and ease the pain that comes with inflamed vessels.

Can low‑dose aspirin prevent strokes in giant cell arteritis?

Yes. Observational data show a 30-40 % reduction in ischemic strokes when low‑dose aspirin is added to standard steroid therapy, without a marked rise in serious bleeding.

Is aspirin safe for children with Kawasaki disease?

High‑dose aspirin (30-50 mg/kg/day) remains the classic regimen for the acute phase, but many centers now switch to ibuprofen after fever control to avoid Reye’s syndrome.

What are the signs of aspirin‑induced gastrointestinal bleeding?

Look for black, tarry stools, vomit that looks like coffee grounds, unexplained anemia, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. Any of these warrant immediate medical attention.

How often should labs be checked while on aspirin therapy?

Baseline CBC, liver enzymes, and creatinine are needed before starting. Re‑check at 2-4 weeks, then every three months if stable.

Can aspirin be combined with other NSAIDs for better pain control?

Generally no. Concurrent NSAIDs increase gastrointestinal and renal toxicity without added benefit. If extra pain relief is needed, consider acetaminophen or a short course of a different NSAID under supervision.

Jordan Levine

October 24, 2025 AT 15:23Aspirin is the unsung hero in the vasculitis battlefield! 💥 It knocks out platelet clumping and douses the fire of inflammation without the steroid side‑effects that make you look like a walking pharmacy shelf. Low‑dose tablets keep the blood flowing smooth while a higher dose throws a punch at prostaglandins. If you’re tired of steroids making you gain weight and break bones, consider adding aspirin to the regimen – just keep an eye on the stomach. The key is dosing: 75‑100 mg for anti‑platelet shield, 300‑500 mg split throughout the day for a real anti‑inflammatory kick. ⚡️

Michelle Capes

October 25, 2025 AT 02:30i totally get the fear of adding another pill when you’re already on steroids 😊 just remember to start low and add a gastro‑protective if you’ve got a sensitive tummy. checking labs every few weeks isn’t a hassle, it’s peace of mind.

Marilyn Pientka

October 25, 2025 AT 13:36One must recognize that the pharmacodynamic profile of acetylsalicylic acid transcends simplistic analgesic narratives. The irreversible acetylation of COX‑1 confers a durable antiplatelet phenotype, yet the dose‑dependent engagement of COX‑2 yields a modest yet clinically pertinent anti‑inflammatory output. In the hierarchy of vasculitic therapeutics, aspirin occupies an adjunctive niche, furnishing thrombo‑prophylaxis whilst tempering cytokine‑mediated endothelial injury. One cannot ethically endorse its monotherapy in lieu of disease‑modifying agents; however, judicious incorporation into a steroid‑sparing protocol aligns with evidence‑based practice. Moreover, the risk‑benefit calculus must integrate gastrointestinal prophylaxis, renal function surveillance, and patient‑specific comorbidities. Ultimately, aspirin’s utility is contingent upon individualized dosing strategies that reconcile hemostatic preservation with inflammatory attenuation.

Kathryn Rude

October 26, 2025 AT 00:43The paradox of inflammation is that the very process meant to heal becomes the agent of destruction. In vasculitis, the vessel wall is both the battlefield and the victim. Aspirin, in its dual COX‑1/COX‑2 inhibition, offers a philosophical compromise: it dulls the pain of the fight without extinguishing the immune response entirely. Yet we must remember that tampering with platelets is akin to removing the guardrails from a steep cliff – one misstep and bleeding ensues. Balance, therefore, is the ultimate virtue in this therapeutic dance.

Lindy Hadebe

October 26, 2025 AT 10:50Meh, another aspirin hype train – same old story.

Ekeh Lynda

October 26, 2025 AT 21:56Aspirin, a simple salicylate derived from willow bark, has traversed centuries to become a cornerstone of modern pharmacotherapy its mechanism of action is elegantly straightforward yet profoundly impactful the irreversible acetylation of the cyclo‑oxygenase enzyme locks the active site rendering it incapable of synthesizing thromboxane A2 thereby reducing platelet aggregation this property alone justifies its widespread use in secondary cardiovascular prevention however the narrative does not end there aspirin at higher doses engages COX‑2 inhibition which curtails the synthesis of pro‑inflammatory prostaglandins this duality positions aspirin as a unique agent capable of addressing both thrombosis and inflammation in vasculitic disorders the clinical data, while not abundant, hints at a beneficial adjunctive role in giant cell arteritis where low‑dose therapy appears to lower ischemic complications the same principle extends to ANCA associated vasculitis where aspirin may mitigate deep‑vein thrombosis risk still the clinician must weigh the gastrointestinal bleeding risk especially in patients already burdened with high‑dose steroids the prophylactic use of proton pump inhibitors or switching to enteric‑coated formulations can ameliorate mucosal injury yet these strategies are not foolproof careful monitoring of hemoglobin, stool occult blood and renal function remains mandatory the patient education component cannot be overstated patients should be instructed to recognize melena, hematemesis or unexplained bruising and seek immediate care the overarching message is that aspirin should not replace disease‑modifying therapies but when integrated thoughtfully into a comprehensive treatment plan it offers modest anti‑inflammatory and anti‑thrombotic benefits that may translate into improved quality of life and reduced steroid exposure

Mary Mundane

October 27, 2025 AT 09:03Sounds reasonable but keep an eye on the gut.

HILDA GONZALEZ SARAVIA

October 27, 2025 AT 20:10From a rheumatology perspective, the decision to add aspirin should start with assessing the patient’s thrombotic risk profile. If they have a history of deep‑vein thrombosis, antiphospholipid antibodies, or active large‑vessel involvement, low‑dose aspirin (81 mg daily) is often justified. For active inflammation, a moderate dose (300‑500 mg divided q6‑8h) can be trialed for a short course, but always alongside a steroid taper to avoid over‑suppression of the immune system. I recommend baseline labs: CBC, BMP, liver enzymes, and a fasting lipid panel. Re‑check CBC and creatinine at 2‑4 weeks, then quarterly. If the patient has a prior ulcer, add a PPI or switch to an enteric coating. Educate them on signs of GI bleed – black stools, coffee‑ground emesis – and advise immediate medical attention if these occur. Finally, document the rationale in the chart: “aspirin added for antiplatelet effect and modest anti‑inflammatory benefit while on steroid taper.”

Amanda Vallery

October 28, 2025 AT 07:16Don't forget to check for aspirin allergy.