Why Blood Thinners Matter More Than You Think

Every year, over 900,000 people in the U.S. are hospitalized for blood clots. Many of them were on anticoagulants - drugs designed to stop clots before they cause strokes, heart attacks, or pulmonary embolisms. But not all blood thinners are the same. For decades, warfarin was the only option. Today, a new generation called DOACs has taken over. And when things go wrong - like a serious bleed - knowing how to reverse these drugs can mean the difference between life and death.

Warfarin: The Old Standard With Big Drawbacks

Warfarin has been around since the 1950s. It works by blocking vitamin K, which your body needs to make clotting factors. Simple, right? But here’s the catch: it’s unpredictable. One person might need 5mg a day. Another might need 10mg. And it changes every week based on what you eat, what pills you take, or even a cold.

That’s why people on warfarin get their blood tested constantly. The goal? Keep the INR between 2.0 and 3.0. Too low, and you’re at risk for clots. Too high, and you could bleed internally. On average, patients get 18 INR tests a year. That’s nearly once every three weeks. Miss a test? Your risk goes up. Eat a big bowl of kale? Your INR drops. Take an antibiotic? It spikes. The system is fragile.

And the cost? Warfarin itself is cheap - as little as $4 a month. But when you add up all the clinic visits, lab fees, and time off work, the real price climbs. Plus, studies show warfarin users have a 35% higher risk of brain bleeds compared to those on newer drugs.

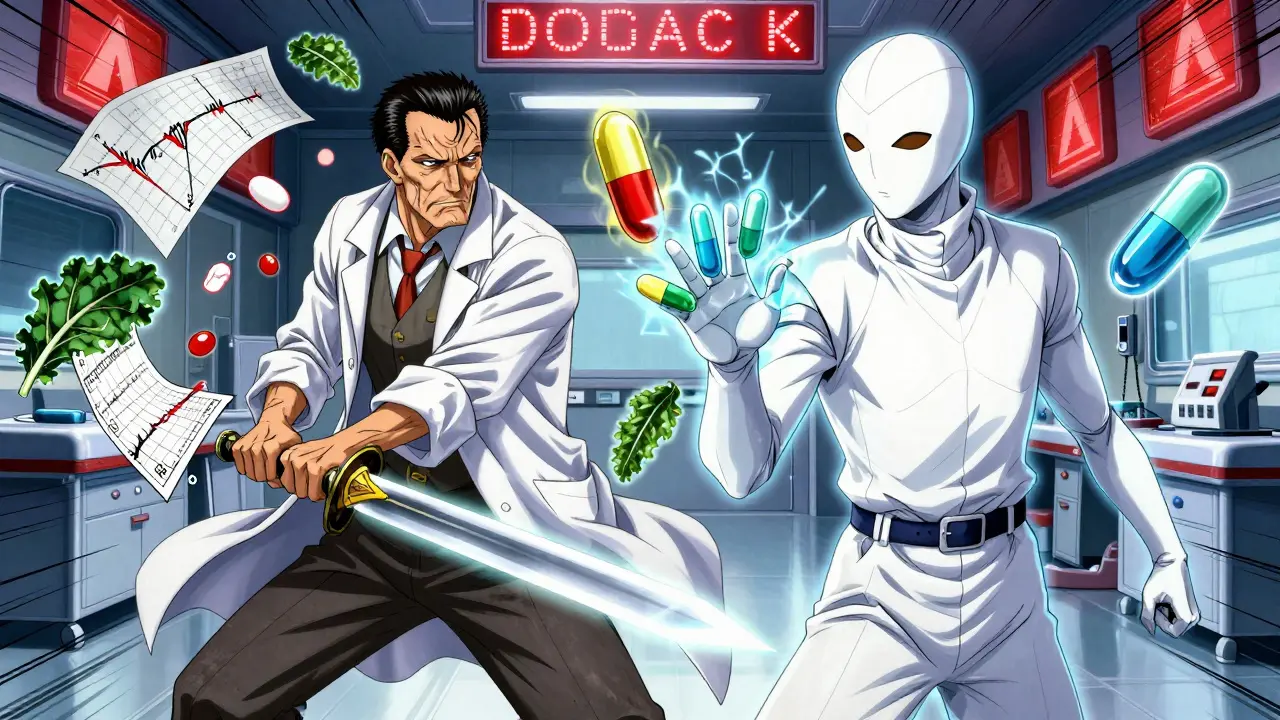

DOACs: The New Normal

Direct oral anticoagulants - or DOACs - are the reason warfarin is no longer first choice for most people. This group includes dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. They work differently: instead of messing with vitamin K, they block specific clotting proteins directly. That’s why they’re more predictable.

No more weekly blood tests. No more worrying about spinach or grapefruit juice. Dosing is fixed: one pill, once or twice a day, depending on the drug. Apixaban, for example, is taken as 5mg twice daily. Rivaroxaban? One 20mg pill a day. Easy.

And the data speaks loudly. A 2023 JAMA study tracking nearly 18,500 patients found those on DOACs had a 34% lower chance of getting another blood clot than those on warfarin. They also had 17% fewer major bleeds. Apixaban, in particular, cut brain bleeds by 35% and lowered death rates by 18%.

DOACs aren’t perfect. They cost more - $300 to $500 a month without insurance. But when you factor in fewer hospital visits, fewer emergency trips for bleeds, and better long-term outcomes, many health systems now say DOACs save money over time.

Who Still Needs Warfarin?

Just because DOACs are better for most people doesn’t mean warfarin is obsolete. There are three key situations where warfarin still wins:

- Mechanical heart valves: DOACs can cause clots on these devices. Warfarin is the only approved option.

- Severe kidney failure: If your eGFR is below 15, DOACs aren’t cleared from your body properly. Warfarin is safer here.

- Antiphospholipid syndrome: This autoimmune condition makes clots more likely. Warfarin works better than DOACs for these patients.

Doctors also still use warfarin in rare cases where DOACs aren’t covered by insurance, or when a patient has been stable on it for years with no issues. But for 85% of new patients with atrial fibrillation or deep vein thrombosis? DOACs are the standard now.

What Happens When You Bleed? Reversal Agents Explained

Any blood thinner can cause a dangerous bleed. The question isn’t whether - it’s how fast you can fix it.

With warfarin, we’ve had tools for decades. Vitamin K reverses the effect over hours. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) gives clotting factors quickly. But the best option? Prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC). It works in under 30 minutes. Emergency rooms stock it. It’s reliable.

DOACs didn’t have reversal agents at first. That was a big worry for doctors. Now they do - but they’re expensive and not always available.

- Idarucizumab (Praxbind®): This drug instantly reverses dabigatran. It’s a monoclonal antibody - think of it as a molecular sponge that grabs dabigatran and pulls it out of your blood. In studies, it worked in 99% of cases. Cost? $3,400 per vial.

- Andexanet alfa (Andexxa®): This reverses factor Xa inhibitors - rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban. It’s a modified version of the clotting factor itself. Works fast, but costs $17,000 per treatment. Many rural hospitals don’t keep it on hand.

- 4-factor PCC: Used when specific agents aren’t available. It helps, but it’s not as effective as the targeted drugs. Still better than nothing.

Here’s the reality: only 62% of U.S. hospitals stock idarucizumab. In small towns, if a patient on apixaban starts bleeding, doctors might have to transfer them an hour away. That delay can be deadly.

Cost, Access, and the Hidden Problem

DOACs are better - but not everyone can afford them. Medicare patients report that 34% skip doses or cut pills in half because of the price. That’s four times higher than for warfarin. Some take half-doses to save money. That’s dangerous. Underdosing leads to clots. Overdosing leads to bleeds.

Insurance companies sometimes make it hard to get DOACs. They’ll force you to try warfarin first - even though guidelines say DOACs are safer. That’s called step therapy. It’s a bureaucratic hurdle that puts lives at risk.

And here’s a surprising fact: 47% of community doctors still think DOACs need regular INR testing. They don’t. That misconception leads to unnecessary tests, confusion, and even patients being switched back to warfarin for the wrong reasons.

What’s Next? The Future of Blood Thinners

The next wave is coming. Ciraparantag - a universal reversal agent - is in late-stage trials. If approved, it could reverse all DOACs and even heparin with one shot. That would be huge.

Another promising drug is milvexian. It blocks factor XIa, a protein that helps clots form but doesn’t play a big role in stopping bleeding. Early results show it cuts bleeding risk by 46% compared to apixaban. Imagine a blood thinner that prevents clots without making you bleed.

Lower-dose DOACs are already here. Apixaban 2.5mg twice daily is now approved for older, smaller, or kidney-impaired patients. Rivaroxaban 10mg daily works for long-term clot prevention with less bleeding risk.

By 2028, DOACs will make up 82% of the anticoagulant market. Warfarin will be a backup - used only when nothing else works.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on warfarin and doing well - no bleeds, no clots, regular tests - don’t rush to switch. But if you’re struggling with frequent blood tests, dietary restrictions, or interactions with other meds, talk to your doctor about DOACs.

If you’re on a DOAC, know which one you’re taking. Know what to do if you bleed. Keep a card in your wallet with your drug name and dose. Tell family members. Emergency responders need to know what’s in your system.

And if cost is a problem? Ask about patient assistance programs. Many drugmakers offer free or discounted DOACs to those who qualify. Don’t skip doses to save money - that’s riskier than the cost.

Final Thought: It’s Not About the Drug - It’s About the Plan

Anticoagulation isn’t just about picking a pill. It’s about matching the drug to the person. Age, kidney function, weight, other meds, lifestyle, cost, access to care - all of it matters. The best anticoagulant is the one you can take safely, consistently, and without fear.

For most people today, that’s a DOAC. But the old rules still apply: monitor your symptoms, know your risks, and never stop without talking to your doctor.

Are DOACs safer than warfarin?

Yes, for most people. DOACs reduce the risk of stroke and major bleeding by 17-35% compared to warfarin, especially brain bleeds. They also don’t require frequent blood tests or dietary restrictions. However, they’re not safer for everyone - people with mechanical heart valves, severe kidney failure, or antiphospholipid syndrome still need warfarin.

Can you reverse DOACs like you reverse warfarin?

Yes, but differently. Warfarin is reversed with vitamin K, FFP, or PCC. DOACs have specific reversal agents: idarucizumab for dabigatran and andexanet alfa for factor Xa inhibitors like rivaroxaban and apixaban. If those aren’t available, 4-factor PCC is used as a backup. Reversal is fast with the right drug - but not all hospitals stock these agents.

Why do some doctors still prescribe warfarin?

Three main reasons: cost, specific medical conditions, and insurance rules. Warfarin is cheaper, especially without insurance. It’s also required for mechanical heart valves and certain autoimmune clotting disorders. Some insurers still require patients to try warfarin first before approving DOACs, even though guidelines say otherwise.

Do DOACs need regular blood tests?

No. Unlike warfarin, DOACs have predictable effects and don’t require routine INR monitoring. Doctors may check kidney function once or twice a year, and occasionally test drug levels in special cases (like kidney failure or overdose), but regular blood tests aren’t needed.

What’s the biggest risk with DOACs?

The biggest risk isn’t bleeding - it’s cost and access. Many patients can’t afford DOACs and skip doses. Also, reversal agents are expensive and not always available in rural or small hospitals. Without the right reversal tool, a bleed can become life-threatening faster than with warfarin.

Can I switch from warfarin to a DOAC?

Yes, if your doctor approves it. Most people with atrial fibrillation or deep vein thrombosis can switch safely. The transition is done carefully - you’ll stop warfarin when your INR is below 2.0, then start the DOAC. Never switch on your own. Timing matters to avoid gaps in protection or overlapping effects.

Gaurav Meena

January 29, 2026 AT 20:15Beth Beltway

January 30, 2026 AT 19:40Natasha Plebani

January 31, 2026 AT 16:09Eliana Botelho

January 31, 2026 AT 22:57Rob Webber

February 1, 2026 AT 11:48calanha nevin

February 1, 2026 AT 13:31Lisa McCluskey

February 3, 2026 AT 04:37owori patrick

February 5, 2026 AT 00:17Darren Gormley

February 5, 2026 AT 00:54Diksha Srivastava

February 6, 2026 AT 08:56Niamh Trihy

February 7, 2026 AT 12:22Sarah Blevins

February 8, 2026 AT 21:44